An old memory, timeless advice

TW: This post contains mentions of child sexual abuse, parental abuse, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and involuntary medical hold.

This is a memory that I’d like to share.

When I was sixteen, in the January before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I was kept in hospital for three days against my will. My grandmother had found a suicide note in my room and then called my father, who called the GP’s emergency number, and then picked me up and escorted me to A&E. He brought it with him to the hospital and I knew he was going to show it to the nurse, so I seized what little empowerment I had available and told the on-call psychiatrist that this letter detailed the weekly sexual abuse I had endured from ages eleven to thirteen before she had the chance to read it for herself. I knew she was going to report it to the police, but what I hadn’t expected was being placed on a 72-hour hold for ‘assessment’.

I was put in the pediatric ward, and was by far the oldest child there. I hated the boredom and being treated like a kid, so sat and solved every problem in my A-level maths textbook that I was able to. My dad was there, and although I didn’t realise it at the time, he made the situation so much worse. He brought me the wrong clothes from home and the wrong food - things I was allergic to. He had to call me every time a nurse asked for my birthdate because he could never remember it.

Other children had their parents sleep next to them, all of us in the same room, but my dad went home every night and left me alone so that he could get a proper rest. I hated being woken up in the middle of the night for blood pressure checks and seeing all the young children with various physical issues completely different and less embarrassing than mine, paranoid that every single parent knew why I was there. How could they not, when nurses would go through the theatre of drawing the curtains around me only to ask as loudly as possible if I’d ever self-harmed and when I started feeling suicidal? I could feel the parents’ judgement and curiosity and pity, and could only be thankful that even the oldest among my fellow patients was too young to even begin to understand. I hated every single second of it, and was determined to lie through my teeth to pass the assessment and not be held for a single minute longer than necessary. I just wanted to go to the bathroom by myself again and wear the right clothes.

The kid in the bed next to be was an eight-year-old girl with asthma and breathing issues. Her mum spent every second by her bed, stroking her hair and chatting to her in the few hours she had enough energy to be awake, and curled up in the chair reading while she slept. The mum overheard my dad and I bickering about something political, as we usually did, and chimed in. Over the next two days in which she and I shared that miserable crammed hospital room, I learnt the following things about her:

- she worked in managing heritage sites and was responsible for overseeing the ongoing refurbishment of a massive national landmark,

- she went to UCL instead of Oxford because it was how she expressed her ‘rebellious phase’,

- she was therefore pretty posh,

- she was a staunch feminist and liberal,

- she clearly thought my dad was an asshole (a conclusion I would later come to agree with).

When my dad was there, she’d take my side in our frequent debates about women’s rights. It was the first time I’d had anyone - let alone a highly-educated adult - back me up in such arguments against my dad. I remember feeling like maybe I wasn’t crazy for thinking he was a huge misogynist after all.

When my dad wasn’t there, she spoke to me softly - a far cry from the no-nonsense and brusque attitude my dad was faced with - whilst carefully avoiding any questions about my presumably shitty home life, focusing instead on political thought and aspirations of university. Talking to her was the only comfort available in that overcrowded room of ill children, and I’d like to think that she was similarly comforted in the face of what must have been overwhelming parental worry.

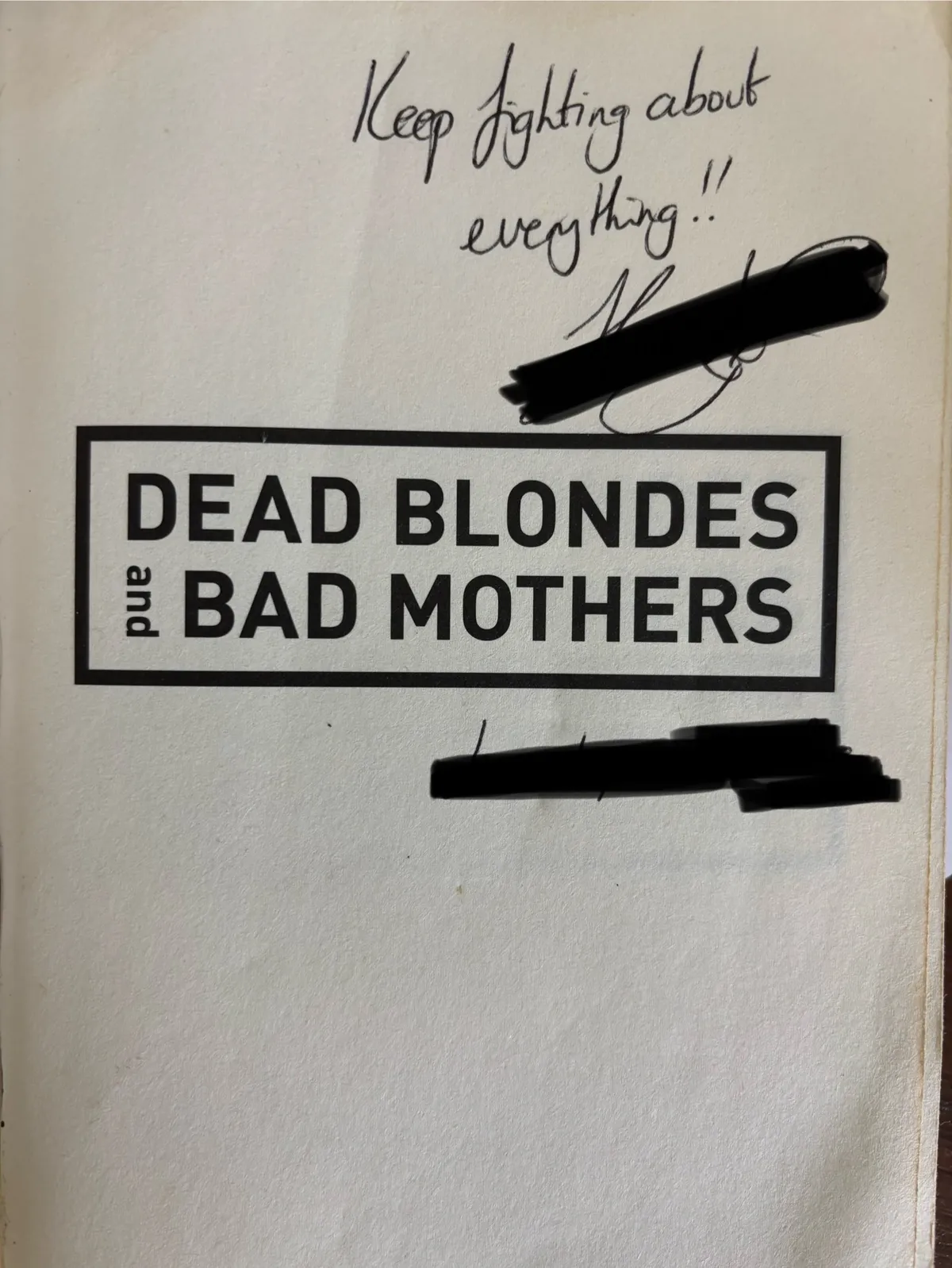

She and her daughter left a day before I did, clearly glad to be rid of the room of coughs and colds and misery. But before she did, she handed me the book she’d been reading - ‘Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers’. It was good and very feminist, she told me, but also very American. I'd get what she meant when I read it. She scribbled a little note on the front page and told me to keep it, ignoring my protests and reassuring me that she could easily get another copy and finish it then. We said our goodbyes and parted ways, two strangers who were able to share a brief moment of connection in such dire conditions.

On the last day of the hold, I had been assured by the psychiatrist that I was eligible for release as he no longer believed I was a risk to myself - my lies had paid off. However, before I was allowed to go, I had to be questioned by two huge police officers about the sexual abuse I had experienced. I hated it, I couldn’t remember anything - I couldn’t remember the perpetrator's name, thoughts of his face made me tense up in panic, and the mere prospect of describing anything even remotely sexual to two unknown men in front of my father was horrifying. But I grasped the book, remembering the little note, and decided that it was the only advice I’d ever seriously follow.

Keep fighting about everything!!